ALOHAnet

ALOHAnet, also known as the ALOHA System,[1][2] or simply ALOHA, was a pioneering computer networking system[3] developed at the University of Hawaii. ALOHAnet became operational in June, 1971, providing the first public demonstration of a wireless packet data network.[4]

The ALOHAnet used a new method of medium access (ALOHA random access) and experimental UHF frequencies for its operation, since frequency assignments for communications to and from a computer were not available for commercial applications in the 1970s. But even before such frequencies were assigned there were two other media available for the application of an ALOHA channel – cables and satellites. In the 1970s ALOHA random access was employed in the widely used Ethernet cable based network[5] and then in the Marisat (now Inmarsat) satellite network.[6]

In the early 1980s frequencies for mobile networks became available, and in 1985 frequencies suitable for what became known as Wi-Fi were allocated in the US. These regulatory developments made it possible to use the ALOHA random access techniques in both Wi-Fi and in mobile telephone networks.

ALOHA channels were used in a limited way in the 1980s in 1G mobile phones for signaling and control purposes.[7] In the 1990s, Matti Makkonen and others at Telecom Finland greatly expanded the use of ALOHA channels in order to implement SMS message texting in 2G mobile phones. In the early 2000s additional ALOHA channels were added to 2.5G and 3G mobile phones with the widespread introduction of GPRS, using a slotted ALOHA random access channel combined with a version of the Reservation ALOHA scheme first analyzed by a group at BBN.[8]

Contents |

Overview

One of the early computer networking designs, development of the ALOHA network was begun in 1968 at the University of Hawaii under the leadership of Norman Abramson and others (including F. Kuo, N. Gaarder and N. Weldon). The goal was to use low-cost commercial radio equipment to connect users on Oahu and the other Hawaiian islands with a central time-sharing computer on the main Oahu campus.

The original version of ALOHA used two distinct frequencies in a hub/star configuration, with the hub machine broadcasting packets to everyone on the "outbound" channel, and the various client machines sending data packets to the hub on the "inbound" channel. If data was received correctly at the hub, a short acknowledgment packet was sent to the client; if an acknowledgment was not received by a client machine after a short wait time, it would automatically retransmit the data packet after waiting a randomly selected time interval. This acknowledgment mechanism was used to detect and correct for "collisions" created when two client machines both attempted to send a packet at the same time.[3]

ALOHAnet's primary importance was its use of a shared medium for client transmissions. Unlike the ARPANET where each node could only talk directly to a node at the other end of a wire or satellite circuit, in ALOHAnet all client nodes communicated with the hub on the same frequency. This meant that some sort of mechanism was needed to control who could talk at what time. The ALOHAnet solution was to allow each client to send its data without controlling when it was sent, with an acknowledgment/retransmission scheme used to deal with collisions. This became known as a pure ALOHA or random-accessed channel, and was the basis for subsequent Ethernet development and later Wi-Fi networks.[4] Various versions of the ALOHA protocol (such as Slotted ALOHA) also appeared later in satellite communications, and were used in wireless data networks such as ARDIS, Mobitex, CDPD, and GSM.

Also important was ALOHAnet's use of the outgoing hub channel to broadcast packets directly to all clients on a second shared frequency, using an address in each packet to allow selective receipt at each client node.[3]

The ALOHA protocol

Pure ALOHA

The first version of the protocol (now called "Pure ALOHA", and the one implemented in ALOHAnet) was quite simple:

- If you have data to send, send the data

- If the message collides with another transmission, try resending "later"

Note that the first step implies that Pure ALOHA does not check whether the channel is busy before transmitting. The critical aspect is the "later" concept: the quality of the backoff scheme chosen significantly influences the efficiency of the protocol, the ultimate channel capacity, and the predictability of its behavior.

To assess Pure ALOHA, we need to predict its throughput, the rate of (successful) transmission of frames. (This discussion of Pure ALOHA's performance follows Tanenbaum.[9]) First, let's make a few simplifying assumptions:

- All frames have the same length.

- Stations cannot generate a frame while transmitting or trying to transmit. (That is, if a station keeps trying to send a frame, it cannot be allowed to generate more frames to send.)

- The population of stations attempts to transmit (both new frames and old frames that collided) according to a Poisson distribution.

Let "T" refer to the time needed to transmit one frame on the channel, and let's define "frame-time" as a unit of time equal to T. Let "G" refer to the mean used in the Poisson distribution over transmission-attempt amounts: that is, on average, there are G transmission-attempts per frame-time.

Consider what needs to happen for a frame to be transmitted successfully. Let "t" refer to the time at which we want to send a frame. We want to use the channel for one frame-time beginning at t, and so we need all other stations to refrain from transmitting during this time. Moreover, we need the other stations to refrain from transmitting between t-T and t as well, because a frame sent during this interval would overlap with our frame.

For any frame-time, the probability of there being k transmission-attempts during that frame-time is:

The average amount of transmission-attempts for 2 consecutive frame-times is 2G. Hence, for any pair of consecutive frame-times, the probability of there being k transmission-attempts during those two frame-times is:

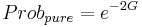

Therefore, the probability ( ) of there being zero transmission-attempts between t-T and t+T (and thus of a successful transmission for us) is:

) of there being zero transmission-attempts between t-T and t+T (and thus of a successful transmission for us) is:

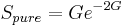

The throughput can be calculated as the rate of transmission-attempts multiplied by the probability of success, and so we can conclude that the throughput ( ) is:

) is:

The maximum throughput is 0.5/e frames per frame-time (reached when G = 0.5), which is approximately 0.184 frames per frame-time. This means that, in Pure ALOHA, only about 18.4% of the time is used for successful transmissions.

Slotted ALOHA

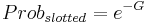

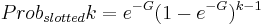

An improvement to the original ALOHA protocol was "Slotted ALOHA", which introduced discrete timeslots and increased the maximum throughput.[10] A station can send only at the beginning of a timeslot, and thus collisions are reduced. In this case, we only need to worry about the transmission-attempts within 1 frame-time and not 2 consecutive frame-times, since collisions can only occur during each timeslot. Thus, the probability of there being zero transmission-attempts in a single timeslot is:

the probability of k packets is:

The throughput is:

The maximum throughput is 1/e frames per frame-time (reached when G = 1), which is approximately 0.368 frames per frame-time, or 36.8%.

Slotted ALOHA is used in low-data-rate tactical satellite communications networks by military forces, in subscriber-based satellite communications networks, mobile telephony call setup, and in the contactless RFID technologies.

Other Protocols

The use of a random access channel in ALOHAnet led to the development of Carrier Sense Multiple Access (CSMA), a 'listen before send' random access protocol which can be used when all nodes send and receive on the same channel. The first implementation of CSMA was Ethernet, and CSMA was extensively modeled in.[11]

ALOHA and the other random-access protocols have an inherent variability in their throughput and delay performance characteristics. For this reason, applications which need highly deterministic load behavior often used polling or token-passing schemes (such as token ring) instead of contention systems. For instance ARCNET was popular in embedded data applications in the 1980s.

Design

Network architecture

Two fundamental choices which dictated much of the ALOHAnet design were the two-channel star configuration of the network and the use of random accessing for user transmissions.

The two-channel configuration was primarily chosen to allow for efficient transmission of the relatively dense total traffic stream being returned to users by the central time-sharing computer. An additional reason for the star configuration was the desire to centralize as many communication functions as possible at the central network node (the Menehune), minimizing the cost of the original all-hardware terminal control unit (TCU) at each user node.

The random access channel for communication between users and the Menehune was designed specifically for the traffic characteristics of interactive computing. In a conventional communication system a user might be assigned a portion of the channel on either a frequency-division multiple access (FDMA) or time-division multiple access (TDMA) basis. Since it was well known that in time-sharing systems [circa 1970], computer and user data are bursty, such fixed assignments are generally wasteful of bandwidth because of the high peak-to-average data rates that characterize the traffic.

To achieve a more efficient use of bandwidth for bursty traffic, ALOHAnet developed the random access packet switching method that has come to be known as a pure ALOHA channel. This approach effectively dynamically allocates bandwidth immediately to a user who has data to send, using the acknowledgment/retransmission mechanism described earlier to deal with occasional access collisions. While the average channel loading must be kept below about 10% to maintain a low collision rate, this still results in better bandwidth efficiency than when fixed allocations are used in a bursty traffic context.

Two 100 kHz channels in the experimental UHF band were used in the implemented system, one for the user-to-computer random access channel and one for the computer-to-user broadcast channel. The system was configured as a star network, allowing only the central node to receive transmissions in the random access channel. All user TCUs received each transmission made by the central node in the broadcast channel. All transmissions were made in bursts at 9600 bit/s, with data and control information encapsulated in packets.

Each packet consisted of a 32-bit header and a 16-bit header parity check word, followed by up to 80 bytes of data and a 16-bit parity check word for the data. The header contained address information identifying a particular user so that when the Menehune broadcast a packet, only the intended user's node would accept it.

Remote units

The original user interface developed for the system was an all-hardware unit called an ALOHAnet Terminal Control Unit (TCU), and was the sole piece of equipment necessary to connect a terminal into the ALOHA channel. The TCU was composed of a UHF antenna, transceiver, modem, buffer and control unit. The buffer was designed for a full line length of 80 characters, which allowed handling of both the 40 and 80 character fixed-length packets defined for the system. The typical user terminal in the original system consisted of a Teletype Model 33 or a dumb CRT user terminal connected to the TCU using a standard RS-232C interface. Shortly after the original ALOHA network went into operation, the TCU was redesigned with one of the first Intel microprocessors, and the resulting upgrade was called a PCU (Programmable Control Unit).

Additional basic functions performed by the TCU's and PCU’s were generation of a cyclic-parity-check code vector and decoding of received packets for packet error-detection purposes, and generation of packet retransmissions using a simple random interval generator. If an acknowledgment was not received from the Menehune after the prescribed number of automatic retransmissions, a flashing light was used as an indicator to the human user. Also, since the TCU's and PCU’s did not send acknowledgments to the Menehune, a steady warning light was displayed to the human user when an error was detected in a received packet. Thus it can be seen that considerable simplification was incorporated into the initial design of the TCU as well as the PCU, making use of the fact that it was interfacing a human user into the network.

The Menehune

The central node communications processor was an HP 2100 minicomputer called the Menehune, which is the Hawaiian language word for “imp”, or dwarf people,[12] and was named for its similar role to the original ARPANET Interface Message Processor (IMP) which was being deployed at about the same time. In the original system, the Menehune forwarded correctly-received user data to the UH central computer, an IBM System 360/65 time-sharing system. Outgoing messages from the 360 were converted into packets by the Menehune, which were queued and broadcast to the remote users at a data rate of 9600 bit/s. Unlike the half-duplex radios at the user TCUs, the Menehune was interfaced to the radio channels with full-duplex radio equipment.

Later developments

In later versions of the system, simple radio relays were placed in operation to connect the main network on the island of Oahu to other islands in Hawaii, and Menehune routing capabilities were expanded to allow user nodes to exchange packets with other user nodes, the ARPANET, and an experimental satellite network. More details are available in [3] and in the technical reports listed in the Further Reading section below.

References

- ^ N. Abramson (1970). "The ALOHA System - Another Alternative for Computer Communications" (PDF). Proc. 1970 Fall Joint Computer Conference. AFIPS Press. http://robotics.eecs.berkeley.edu/~pister/290Q/Papers/MAC%20protocols/ALOHA%20abramson%201970.pdf

- ^ F. Kuo (1995). "The ALOHA system". ACM Computer Communication Review: 25

- ^ a b c d R. Binder; N. Abramson, F. Kuo, A. Okinaka, D. Wax (1975). "ALOHA packet broadcasting - A retrospect" (PDF). Proc. 1975 National Computer Conference. AFIPS Press. http://www.computer.org/plugins/dl/pdf/proceedings/afips/1975/5083/00/50830203.pdf?template=1&loginState=1&userData=anonymous-IP%253A%253AAddress%253A%2B24.130.99.144%252C%2B%255B172.16.161.5%252C%2B24.130.99.144%252C%2B127.0.0.1%255D

- ^ a b N. Abramson (December 2009). "The ALOHAnet – Surfing for Wireless Data" (PDF). IEEE Communications Magazine 47 (12): 21–25. doi:10.1109/MCOM.2009.5350363. http://dl.comsoc.org/livepubs/ci1/public/2009/dec/pdf/abramson.pdf.

- ^ R. M. Metcalfe and D. R. Boggs (July 1976). "Ethernet: Distributed Packet Switching for Local Computer Networks". Comm. of the ACM 19 (7).

- ^ D. W. LipkepkAjay2120 et al. (Fall 1977). "MARISAT – a Maritime Satellite Communications System". COMSAT Technical Review 7 (2).

- ^ B. Stavenow (1984). "Throughput-Delay Characteristics and Stability Considerations of the Access Channel in a Mobile Telephone System". Proceedings of the 1984 ACM SIGMETRICS Conference on Measurement and Modeling of Computer Systems. pp. 105–112

- ^ W. Crowther et al. (January, 1973). "A System for Broadcast Communication: Reservation-ALOHA". Proceedings of the 6th Hawaii International Conference on Systems Sciences. Honolulu. pp. 371–374

- ^ A. S. Tanenbaum (2003). Computer Networks. Prentice Hall PTR.

- ^ L. G. Roberts, Lawrence G. (April 1975). "ALOHA Packet System With and Without Slots and Capture". Computer Communications Review 5 (2): 28–42. doi:10.1145/1024916.1024920.

- ^ L. Kleinrock and F. A. Tobagi (1975). "Packet switching in Radio Channels: Part I – Carrier Sense Multiple Access Modes and their Throughput-Delay Characteristics". IEEE Transactions on Communications (COM–23): 1400–1416.

- ^ Mary Kawena Pukui and Samuel Hoyt Elbert (2003). "lookup of Menehune ". in Hawaiian Dictionary. Ulukau, the Hawaiian Electronic Library, University of Hawaii Press. http://wehewehe.org/gsdl2.5/cgi-bin/hdict?j=pk&l=en&q=Menehune&d=. Retrieved August 11, 2011.

Further reading

- R. Metcalfe, Xerox PARC memo, from Bob Metcalfe to Alto Aloha Distribution on Ether Acquisition, May 22, 1973.

- R. Binder, ALOHAnet Protocols, ALOHA System Technical Report, College of Engineering, The University of Hawaii, September, 1974.

- R. Binder, W.S. Lai and M. Wilson, The ALOHAnet Menehune – Version II, ALOHA System Technical Report, College of Engineering, The University of Hawaii, September, 1974.

- N. Abramson, The ALOHA System Final Technical Report, Advanced Research Projects Agency, Contract Number NAS2-6700, October 11, 1974.

- N. Abramson "The Throughput of Packet Broadcasting Channels", IEEE Transactions on Communications, Vol 25 No 1, pp117–128, January 1977.

- M. Schwartz, Mobile Wireless Communications, Cambridge Univ. Press, 2005.

- K. J. Negus, and A. Petrick, History of Wireless Local Area Networks (WLANs) in the Unlicensed Bands, George Mason University Law School Conference, Information Economy Project, Arlington, VA., USA, April 4, 2008.

External links

- Dynamic Sharing of Radio Spectrum: A Brief History

- Funding a Revolution: Government Support for Computing Research

- ALOHA to the Web, Norman Abramson, HICCS Distinguished Lecture

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||